This post is the summary of the book called Understanding Distributed system by Roberto Vitillo.

Chapter 1: Introduction

Fundamental challenges of distributed system

- Communication

- Coordination

- Scalability

- Resiliency

- Operations

Coordination: It’s a very hard challenge to coordinate multiple nodes into a single coherent in the presence of failures.

Resiliency: System availability is defined as the amount of time the application can server request divided by the duration of the period measured. Availability often describe with nines. Three nines are typically considered acceptable, and anything above four is considered highly available.

Chapter 2: Reliable links

2.1 Reliability

- TCP partitions a byte stream into discrete packets called segments.

2.2 Connection lifecycle

- The opening state, in which the connection is being created.

- The established state, in which the connection is open and data is being transferred.

- The closing state, in which the connection is being closed.

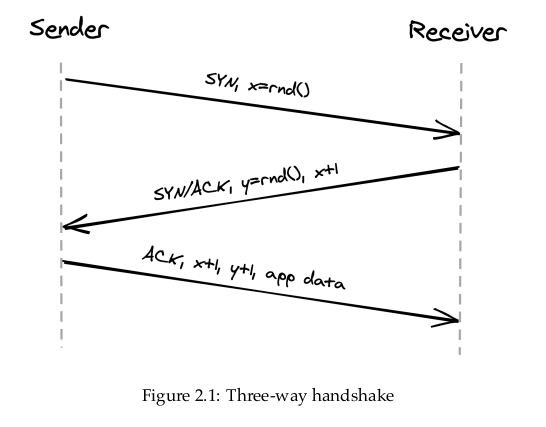

TCP uses a three-way handshake to create a new connection:

- The sender picks a random sequence number x and sends a SYN segment to the receiver.

- The receiver increments x, chooses a random sequence num ber y and sends back a SYN/ACK segment.

- The sender increments both sequence numbers and replies with an ACK segment and the first bytes of application data.

2.3 FLow Control

- Flow control is a backoff mechanism implemented to prevent the sender from overwhelming the receiver.

- The sender, if it’s respecting the protocol, avoids sending more data that can fit in the receiver’s buffer.

- TCP is rate-limiting on a connection level.

2.4 Congestion control

- When a new connection is established, the size of the congestion window is set to a system default. Then, for every segment acknowledged, the window increases its size exponentially until reaching an upper limit.

- When the sender detects a missed acknowledgment through a timeout, a mechanism called congestion avoidance kicks in, and the congestion window size is reduced.

2.5 Custom protocols

TCP’s reliability and stability come at the price of lower bandwidth and higher latencies than the underlying network is actually capable of delivering.

- Unlike TCP, UDP does not expose the abstraction of a byte stream to its clients. Clients can only send discrete packets, called datagrams, with a limited size.

- UDP doesn’t implement flow and congestion control either.

Chapter 3: Secure links

3.1 Encryption

Encryption guarantees that the data transmitted between a client and a server is obfuscated and can only be read by the communicating processes.

3.2 Authentication

- TLS implements authentication using digital signatures based on asymmetric cryptography.

- One of the most common mistakes when using TLS is letting a certificate expire

- Automation to monitor and auto-renew certificates close to expiration is well worth the investment.

3.3 Integrity

- TLS verifies the integrity of the data by calculating a message digest. A secure hash function is used to create a message authentication code(HMAC).

- The TLS HMAC protects against data corruption as well, not just tampering.

- While TCP does use a checksum to protect against data corruption, it’s not 100% reliable.

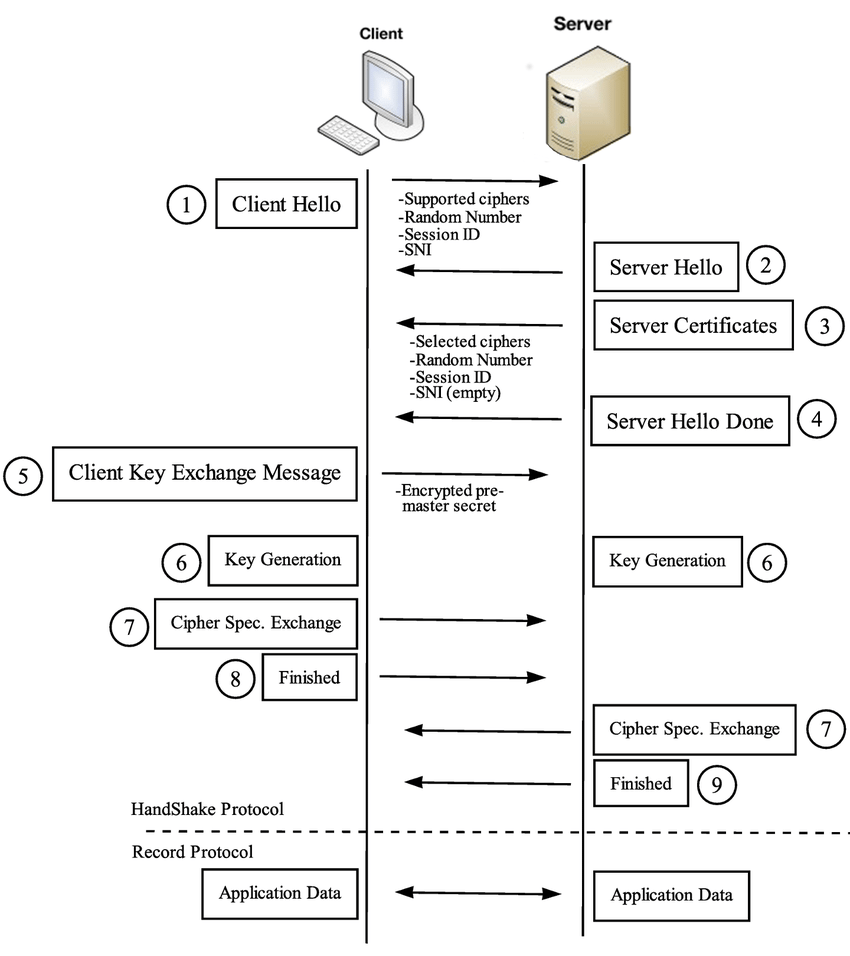

3.4 Handshake

- The handshake typically requires 2 round trips with TLS 1.2 and just one with TLS 1.3

Chapter 4 : Discovery

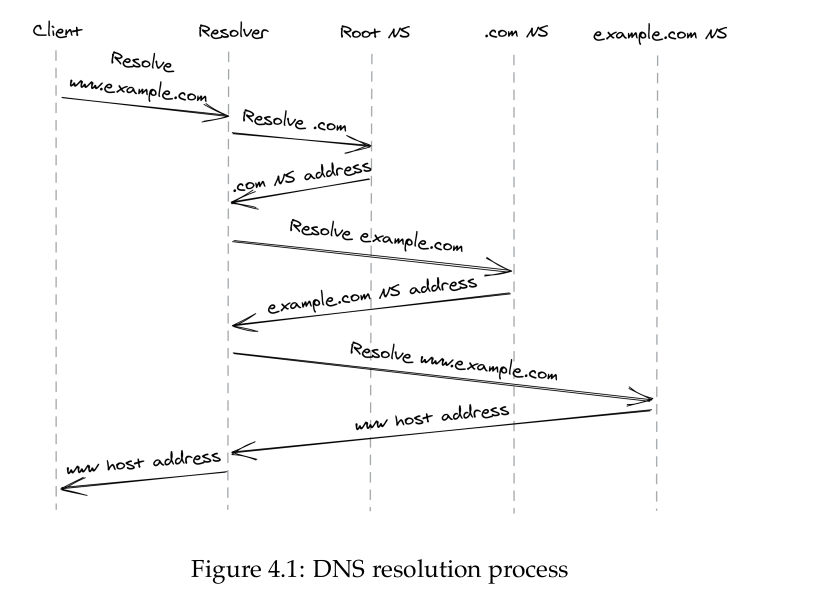

the Domain Name System (DNS) — a distributed, hierarchical, and eventually consistent key-value store.

- The DNS resolver is typically a DNS server hosted by your Internet Service Provider.

- DNS uses UDP to serve DNS queries as it’s lean and has a low overhead.

- the industry is pushing slowly towards running DNS on top of TLS.

- the browser, operating system, and DNS resolver all use caches internally.

- Every DNS record has a time to live (TTL) that informs the cache how long the entry is valid

- DNS can easily become a single point of failure if your DNS name server is down and the clients can’t find the IP address of your service, they won’t have a way to connect it. This can lead to massive outages

Chapter 5: APIs

5.1 HTTP

In HTTP 1.1, a message is a textual block of data that contains a start line, a set of headers, and an optional body:

- In a request message, the start line indicates what the request is for, and in a response message, it indicates what the response’s result is.

- The headers are key-value pairs with meta-information that describe the message.

- The message’s body is a container for data.

HTTP 2 9 was designed from the ground up to address the main limitations of HTTP 1.1. It uses a binary protocol rather than a textual one, which allows HTTP 2 to multiplex multiple concurrent request-response transactions on the same connection.

5.2 Resources

URLs should be kept simple, even if it means that the client might have to perform multiple requests to get the information it needs.

5.3 Request methods

An idempotent method can be executed multiple times, and the end result should be the same as if it was executed just a single time.

5.4 Response status codes

Status codes between 200 and 299 are used to communicate success. For example, 200 (OK) means that the request succeeded, and the body of the response contains the requested resource.

Status codes between 300 and 399 are used for redirection. For example, 301 (Moved Permanently) means that the requested resource has been moved to a different URL, specified in the response message Location header.

Status codes between 400 and 499 are reserved for client errors. A request that fails with a client error will usually continue to return the same error if it’s retried, as the error is caused by an issue with the client, not the server.

Status codes between 500 and 599 are reserved for server errors. A request that fails with a server error can be retried as the issue that caused it to fail might be fixed by the time the retry is processed by the server.

5.5 OpenAPI

The OpenAPI specification, which evolved from the Swagger project, is one of the most popular IDL for RESTful APIs based on HTTP.